Most of the time I portray a moderately high-status c.600 CE Langobard man in what is now northern Italy. Where I live in real life, there are very few other people reenacting this particular period, and I am usually the only Langobard at events I attend. On the other hand, there are many, many people here who do Viking-Era Norse reenactment and it’s enough of a mixed bag as far as Hiberno-Norse, Eastern Scandinavia, Danish, etc. that if I wanted to show up at a “Viking”-specific event and not look out of place, I have a lot of leeway as long as my kit is somewhere between 800 and 1100 CE and from somewhere vaguely near the North Sea. So this project essentially started as a way to have a “Viking Age” kit in my back pocket if I ever need one. Of course, I wanted to make sure that whatever I came up with was coherent and consistent and that all the elements were documentable to a specific region within a relatively tight timeframe, and I am also a little bit of a contrarian – so I instead of Scandinavia, I decided to focus on Frisia in the 9th century.

Why Frisia?

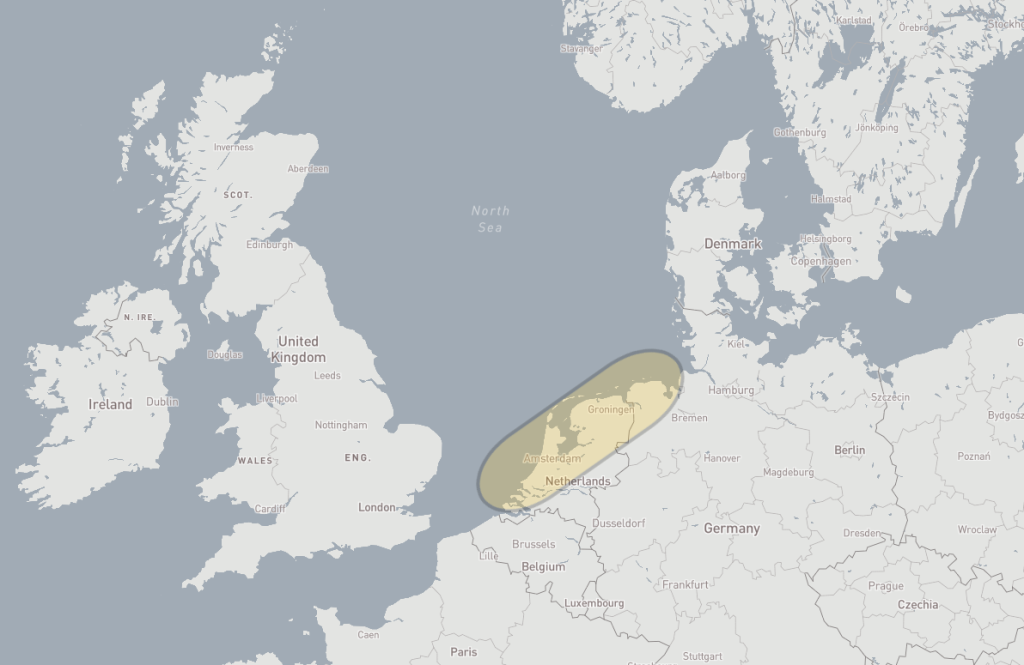

For much of the 300-year period often termed the “Viking Age,” Frisia played an important role in regional commerce. Located on the northern coast of Europe between the kingdoms of the Danes and the Franks, historically the Frisian coast spanned the approximate area from modern-day Bruges to Bremen – see map below (a much larger area than the present province of Friesland in the Netherlands). We have ample evidence of trade across the North Sea to Britain and Scandinavia and it seemed like an good premise for an outfit that might have to rub shoulders with Anglian/Saxon or Norse reenactors.

The other appeal is that this is a region with a decent number of textile and leather finds from this general period, so I have some source material to draw upon for many of the garments. I need to supplement it with material from neighboring areas as well, but don’t need to extrapolate an entire outfit from non-Frisian sources. I settled on the year 850 CE to try to focus things a bit and put myself solidly in the middle of the “Viking Age” – although in this case, I prefer to think of it as the Carolingian period; Frisia had become part of the Holy Roman Empire in the 8th century and was pretty thoroughly Christianized by the 790s.

Overview

So where to start? For this little project, I set out to assemble one complete set of soft kit for a free man of modest means – someone who lived in one of the trading towns, but not a wealthy merchant. Perhaps an artisan producing non-luxury items, such as a shoemaker or boneworker. This presentation requires no weapons or fancy jewelry, just a set of sturdy, well-made clothing using relatively affordable materials. Based on what we know of men’s fashion at the time, the ensemble would have been similar to what was worn in many parts of Europe, and would likely include a wool tunic and trousers, a pair of shoes and leg-wraps, a set of linen undergarments, a wool cloak, as well as some basic accessories like a belt, utility knife, a cap, and a cloak pin or brooch (Brandenburgh, 2016). The following discussion covers each of these components (aside from linen undergarments and utility knife) and explains how I arrived at my decisions in reconstructing the ensemble.

Materials

To remain on the side of caution if I ever find myself at an event with strict living-history authenticity standards, I also wanted to make sure whatever I put together meets or exceeds the requirements outlined in Regia Anglorum’s kit guide (I use this as a reference point simply because theirs are the most stringent kit requirements I can find online). As with my Langobard kit, everything is hand-sewn using wool fabric and thread, with vegetable-tanned leather and linen thread for shoes and accessories. While the fabrics are mostly machine-woven, I’ve tried to use natural dyes where possible or close synthetic approximations when I can’t. The only items I actually had to purchase were the cloak pin and cloak.

Available vs. common

In addition, it was important to me to make choices that were consistent with the portrayal of a lower-status individual. This meant that I wanted to make sure that all the elements were things likely to be accessible to someone who was not wealthy or well-traveled. On the one hand, that saved me the expense of having to source replica weapons, jewelry, or belt hardware, but on the other hand, it meant I had to look carefully at the archaeological evidence to see what items and materials would have been common in period, rather than simply available if money were no object.

Artistic depiction?

In addition to the archaeological material discussed in the following sections on each garment, I also looked to artistic depiction to help guide the process. While not a Frisia-specific source, the Stuttgart Psalter is one of the best-known Carolingian manuscripts and is believed to have been produced in Paris around 820. It depicts a huge range of subjects, and it is worth noting that Carolingian manuscripts are quite problematic in their rendering of heroic figures – following earlier tradition, they are often shown wearing “classical” armor that does not match finds of actual armor from the same period (so, probably not a good basis for recreating armor and fighting kit). Rather than try to make inferences based on the clothing of nobles, soldiers, clergy, or persons clearly meant to represent foreigners or historical/biblical figures, I tried to focus on the comparatively smaller number of images of ordinary people doing everyday tasks, wearing clothing and accessories that can be corroborated by contemporary archaeological finds.

This image of a man plowing (112 v) is a great example of this. He wears a tunic that hits above the knee when belted and rucked a bit, and the artist seems to be indicating the folds of the sleeves and body without any other adornment – he does not have any of the decorative neckline or hem facings shown on higher-status figures. His cloak seems to be doubled and clasped at the right shoulder with a small round brooch and does not seem to have any visible fringe or trim. What little we can see of his upper legs may indicate fitted trousers or leggings beneath the tunic, and the lines on his lower legs may represent fabric strips wrapped in a spiral, much like the legwraps or winingas worn by Anglian/Saxon and Norse people of the same period.

Garments

The Tunic

For a tunic, there are no complete extant garments specific to this area, but Dutch archaeologist Chrystel Brandenburgh has published an analysis of hundreds of textile fragments from 31 sites in coastal areas of the Netherlands that provides information on weave pattern, dying, stitching, and to a limited extent, construction. A fragment from Middelburg, a site active between 875 and 1000 CE, includes a sleeve fragment and a triangular gore or gusset (Brandenburgh, 2010). While not enough to base an entire tunic on, it lends support to the idea that tunics from this region would mirror contemporary finds from northern Europe more broadly and use a typical early medieval construction with triangular gores inserted to shape a garment otherwise made up of rectangles. Thus I created a generic, plain tunic with a round neckline and large triangular side gores.

Of note, I have omitted the little square gusset many reenactors use in the armpit of Viking Age tunics. [UPDATE: rather than enumerate all the finds, I recommend checking out this recent article by Tomáš Vlasatý–the short version is that the northern European finds that use this small gusset are from the 11th century, such as the Viborg shirt and the Skjoldhamn tunic, or are even later. Other examples use different solutions or simply do without it]. Although some earlier tunics from Egypt use this type of gusset, it does not appear to be well supported by extant garments from northern Europe as early as the 9th century. It is not strictly necessary for range of motion, especially when the tunic body is cut with positive ease, since this places the shoulder seam closer to the deltoid-bicep junction. I can easily row a boat in this tunic without stressing the armpit seams (yes, I tested this). Like the Stuttgart Plowman’s tunic, it hits a bit above the knee when belted and the sleeves are fairly close-fitting. The sleeves are long enough to cover the base of the thumb, but taper from elbow to a fairly snug wrist opening. This keeps the cuff above my hand unless I deliberately tug it down, and the slight excess fabric creates the folds we see in the Stuttgart Psalter.

As far as materials go, I selected a 2/2 wool twill with 11×9 threads/cm. One sleeve fragment from Leens was woven from a plain 2/2 twill with 8×5 threads/cm, while others were somewhat finer. This puts mine within the parameters of weave and thread count that Brandenburgh documented as parts of sleeved garments. All sleeve fragments Brandenburgh mentions were sewn with a fairly thin plied yarn, so I stitched it with a two-ply 2o/2 wool yarn. As far as color, dyer’s madder was present in the northern part of the Netherlands in the Early Middle Ages, and woad and weld were also known in the region dating back as far as Roman occupation and the Iron Age (Brandenburgh, 2010). In addition to these sources for red, blue, and yellow, Brandenburgh noted that other locally available dyes included brown tones derived from nuts or bark, although these are harder to detect in excavated textiles. I chose to use wool in a tan color that is easily achievable with the bark of several types of trees native to the Netherlands, and the fabric shows the very slight variation in the underlying color of the natural wool.

The Cap

The cap is my favorite part of the whole ensemble, and is part of what creates a distinctive Frisian outfit. For this component, I also had the benefit of several intact examples to work from, so I could make a closer reconstruction of a specific item. Early medieval Frisian settlements have yielded multiple examples of hats with ear or neck-flaps, including finds from Aalsum, Oostrum, Rasquert, and Leens (Brandenburgh, 2010). I am particularly fond of the Rasquert cap, which was dated between 800 and 900 CE and is thus perfect for this project. The construction methods and materials are described in detail in two published articles, so between those and a good-quality photograph I was able to reconstruct the hat fairly closely, including the various structural and decorative stitch types.

The original used a finer quality diamond-twill fabric than mine, which is a coarser weave and slightly different warp-to-weft ratio, but in both respects the fabric I used is still within the parameters of several of the other similar hat finds. I was not able to obtain a fabric with the exact same warp and weft count as the Rasquert cap, which has an extremely high warp/weft ratio (17 x 9 threads per cm) resulting in a more elongated diamond, but I was able to find an undyed diamond twill in a 12 x 11 thread per cm weave that closely resembled the weave of the Aalsum cap, which has a fairly even warp/weft ratio (10×8 threads per cm) and a more square shape to the diamond repeats. Overall, the thread counts of the Frisian caps ranged from 8 x 7 to 14 x 12, and the Rasquert cap is the outlier for both the fineness of its weave and the high warp/weft ratio (Brandenburgh, 2010, 66-69). Although I was not able to match the Rasquert cap itself, the fabric I selected is within the range displayed by the other similar caps as far as thread count and warp/weft ratio.

Neither of the two available publications state what color the Rasquert hat originally was, other than to note that the decorative stitching still retains traces of a red color (Zimmerman, 2010, 288). Analysis of a sampling of Early Medieval textiles from the Netherlands found that most of the diamond twill fabrics tested were made from naturally dark brown or black fleeces (Brandenburgh, 2010, 48). The Oostrum hat, however, was made from a natural white wool and analysis found that it was originally dyed a light red color with a darker red wool for the decorative stitching. This color was likely produced with madder (Rubia tinctorum), although bedstraw (either Galium mollugo or Galium verum) was also known in the Early Medieval period (Brandenburgh, 2010, 54). I had no prior experience with natural dyeing, so I wanted to try something fairly uncomplicated (i.e. easy dyebath preparation and no mordant required) for my first attempt, and the onion dye produced a comparable shade to bedstraw or madder (Dean 54, 77).

The darker red thread used for the decorative stitches was commercially dyed, as I was not able to get a more vibrant shade from the onion dye. and like the original, the decorative stitching (see Zimmerman 2010, p.288 for all stitch details) incorporates two red threads twisted into the structural whipstitching around the crown and the vertical seam, as well as in a single line of red backstitch used to topstitch the lower edge of the hat and neck flap. My seam allowances are not quite as small as the originals (I increased them from 5mm to about 8mm since my thread count was a little lower), but are secured with the same overcast stitch.

Decorative stitching and finished hat.

While many of the pillbox hats from this period seem to be more strictly cylindrical in their construction (oval top, uniformly rectangular strip forms the sides), the Rasquert cap has a slightly more fitted shape. This turned out to be the result of two design features that can be observed in the original photograph: the sides are cut with a very slight bias, achieved by curving the upper and lower edges of the panel, and the height of the sides is greater in the back than in the front. This in turn results in a crown circumference that is less than the circumference at the lower hem of the side panels, and the hat acquires more of the rounded shape of the wearer’s head. Although the flap appears fairly short in the published image, scholar Hanna Zimmerman examined the hat and notes that the flap is “folded inwards several times so that it appears smaller than its actual size” (Zimmerman, 2010, p.289). She does not provide an actual dimension, but based on other similar finds, the flaps all seem to be long enough to cover the ears and nape of the neck, so that is how long I made mine.

The Trousers

For the trousers, I had no clear model to follow. Fragments from Haithabu seem to support a crotch construction similar to the much earlier Thorsberg trousers (Hägg et al. 1984) and Carolingian artistic depictions like the Stuttgart Psalter don’t offer much detail of this area other than to suggest that legwear is rather form-fitting and mostly hidden. There is some evidence for early separate hose at Haithabu, although those are probably from about a hundred years later than my target date. My Frisian man wears a pair of tight wool trousers using a Thorsberg crotch construction in a lightly mottled natural gray 2×2 twill with a thread count similar to the tunic. For the six inches that will be visible, this seems like a decent compromise for now – the overall fit matches the artistic depictions, and the crotch construction was apparently in use at the time.

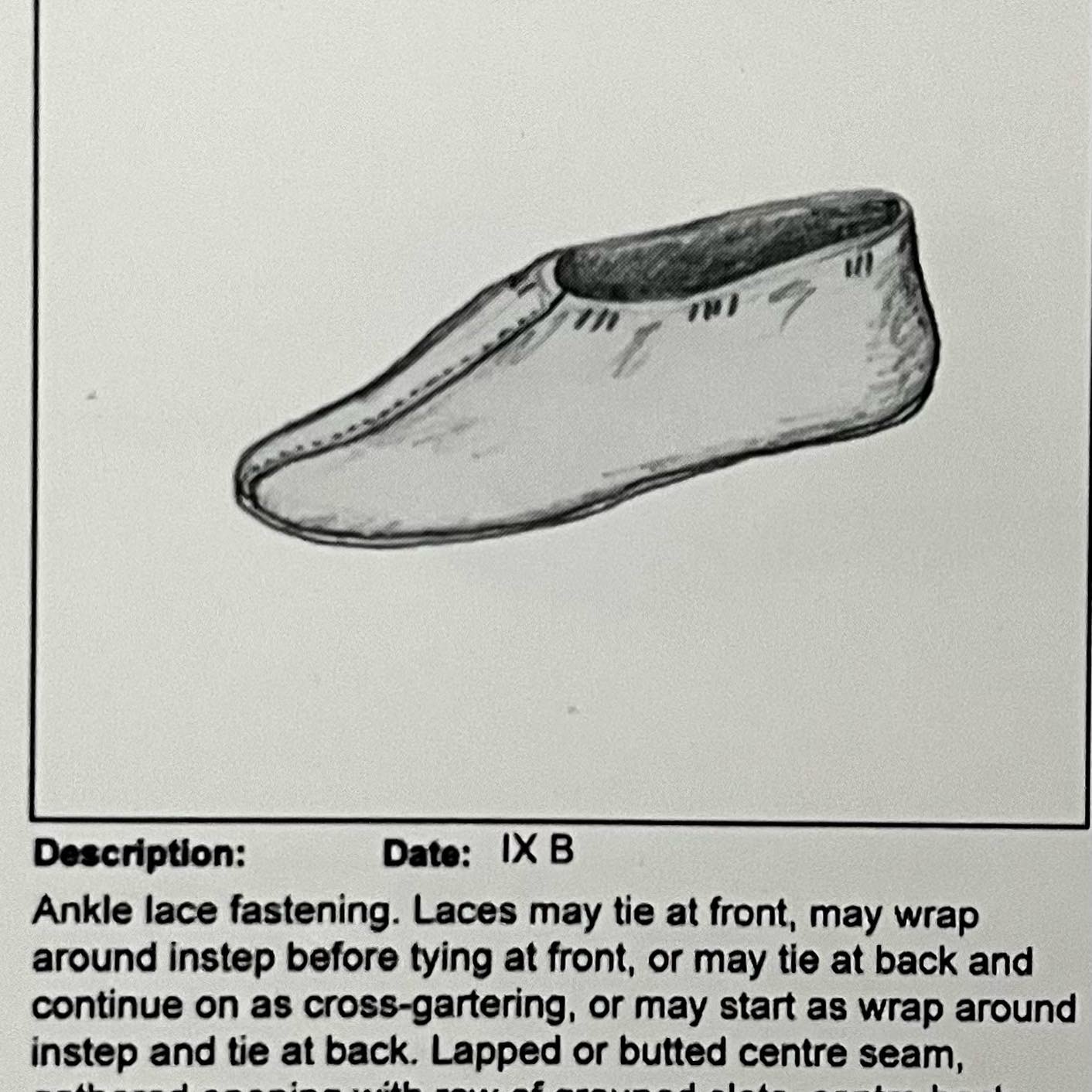

The Shoes

For shoes, I had several choices. Back when I put together Viking Era Footwear Finder, I mapped more than 20 known shoe finds in Frisian territory that were intact enough to reconstruct the style. Within my target timeframe, there are a few examples of toggled ankle shoes, but also many variations of a low shoe with a top seam down the instep and a single line of lacing around the ankle (Volken, 2016). Some of this latter type seem to be more fitted (see the style classified by calceologist Marquita Volken as ‘Elisenhof’), while others have generously-cut uppers that are gathered by the lace to create either multiple slight pleats (see Volken’s ‘Wolin’ and ‘Gniezno’ styles) or a single prominent fold-over at the instep (see Volken’s ‘Wijk’ style) when tied. Although at some point I do want to make a pair of ‘Wijk’ style shoes, they seem to date from a tad earlier than my target period so I decided to go with one of the ‘Wolin’ variants, using a central lapped seam on the instep and a front-tying closure that spreads out the gathers in the upper. I made mine from a medium-weight vegetable tanned goatskin upper, a thicker cowhide sole, and calfskin lacing at the ankles. I sewed them with waxed linen thread and finished them with tallow.

My shoes based on the Wolin style turnshoe, drawing from Marquita Volken’s Archaeological Footwear.

The Legwraps

As for the legwraps, the leg/footwear depicted in the Stuttgart Psalter is a mixed bag, and it’s hard to say how reliable it is for my purposes – none of the shoe styles supported by evidence from the North Sea coast seem to appear in the Psalter, and many of the courtiers and soldiers seem to be wearing some kind of tall boot with a rolled or dagged top edge (is this a real style? or is it artistic license like the armor? 5th century ivories show a type of footwear that subsequent generations of artists could easily have simplified and stylized into such a design). These “boots” sometimes show a spiral line as well, although they are just as often decorated in some other way and are generally depicted in a different color than the rest of the legs. The Stuttgart plowman’s leg coverings, on the other hand, seem to go all the way to the knee and have no delineated upper edge, so whatever is going on there doesn’t look like the boots shown on some other figures. It is certainly possible for me to get a comparable stocking-like full coverage of my lower leg and foot using a 10cm leg wrap or wininga about 2.5 meters long, but I’m not sure how much to read into this detail.

Fortunatly, in nearby Elisenhof, a coastal settlement due north of Bremen, excavations have yielded multiple finds of winingas dated to the 8th century (Hundt, 1981), so I am comfortable with including this garment as part of my ensemble. The examples from Elisenhof, as well as numerous fragments recovered at Haithabu, are all narrow strips of herringbone twill woven to width, typically measuring between 7 and 10 cm wide (Hagg 1991). I already had a spare pair hanging around, made of a natural light-colored wool in a 10cm-wide herringbone twill. They are now rather grubby; as soon as spring arrives and I can harvest fresh nettles, I plan to dye these (aiming for a green-gray color, but I’ll take what I can get).

The Belt

So that takes care of the hat, tunic, trousers, legwraps, and shoes. What’s left? Oh right, the belt. I decided that my Frisian will wear an entirely organic belt set. There is plenty of evidence for bone and antler buckles during this period, and for all we know, they may have been even more common but less likely to survive in the ground. Here’s a great overview of the genre if you are curious. As my exemplar, I started with a Carolingian bone buckle excavated from a terp (settlement) mound at Dongjum (Roes 1964). It is quite small, just over 50mm long, and is missing its tongue. I had to modify the decorative scheme slightly since I only have an auger sized for a 5mm ring-and-dot motif rather than the much smaller one used for the Dongjum buckle. I also had to guess at the shape of the missing buckle tongue. I’ve seen one reconstruction of this that uses a metal wire tongue, but I was able to make a bone one that fits just fine despite the small space, and a bronze pin holds it in place. The strap end is conjectural, since the Dongjum find did not include a matching end. It may never have had one, but I decided I could always cut this one off if I have a change of heart. In keeping with period depictions that rarely show a strap end, the strap is fairly short and the whole thing will not be especially visible beneath the tunic overhang.

My buckle, with rapid test for scale (yes, I am writing this in the midst of the Omicron variant surge) and the example from Dongjum at top right (Roes 1964).

The belt strap itself is of thin vegetable-tanned goathide, about a 2.5 oz. weight, and is doubled over with a whipstitched seam down the back. The leather is then dampened and pressed flat with a rib bone to smooth it. There is evidence for this type of construction, including strap fragments from York and Haithabu, and it is an effective way to use a low-quality hide, since the seam provides extra structure. While a half-inch belt made this way would not be ideal for a seax or sword, for a belt that is primarily used to cinch a tunic and suspend nothing more than a small utility knife, purse, and maybe a whetstone, it is more than adequate.

The Cloak and the Brooch

The cloak and brooch are important items to consider; these are two items I had to purchase rather than make, and figuring out what I needed to source involved a lot more complex consideration and hypothesizing. What follows is essentially a walkthrough of my decision-making process as I considered my options.

Cloak

During this period, Frisia was known for its textile exports, particularly the high-quality fabric known as pallia Fresonica. But would a man of modest means be wearing a valuable trade good for warmth? It seems unlikely. At the same time, the cloak was a vital piece of outerwear and our Frisian man need not spend his winters walking around in a thin, undyed blanket either. As noted earlier, madder, woad, and weld were all known in the region during this period, as well as a variety of dyestuffs derived from nuts or bark (Brandenburgh 2010). The ploughman from the Stuttgart Psalter wears a bright red cloak, and even allowing for artistic convention and the desire to use bright colors and good visual contrast rather than illustrating things exactly as they were, it is worth noting that the painter had plenty of choices of color and opted to render this ordinary man in an obviously dyed garment – even if such a person might not have worn one with such a richly saturated color in real life.

While I have seen some reenactors insist that anyone not portraying a member of the nobility or warrior elite should err on the side of caution and wear only undyed garments, I will also throw out a bit of my non-scholarly opinion here – I consider the enormous amount of labor that goes into processing fleece, producing yarn, and weaving cloth by hand versus how long it has taken me to whip up a batch of one of the less complicated dye options using foraged plants or kitchen waste and shove wool into it (spoiler alert: not very long, and aside from periodic stirring, a lot of it is non-active time during which I could spin or chop wood or do other needful work). Not to mention the fact that one dye bath can be used repeatedly (albeit with gradually diminishing results), thus spreading out the value of the dyestuff and labor over multiple finished objects. Given the abundance of wild and domesticated plants that yield dyestuff and the documented human propensity to make things pretty, it was almost inconceivable to me that an Early Medieval person who could afford the expense of a new cloak measuring roughly two square meters could not also afford to have it be a colored one – not necessarily a richly saturated garment made using more valuable dyestuffs in a strong bath or with multiple dips, but at least a quick dip in a partially exhausted vat.

BUT…

On the other hand, the color of the fleece likely influenced this choice and not all wool is naturally white; Brandenburgh also references Penelope Walton Rogers work with Anglian/Saxon textiles and notes that within the larger body of textile finds from Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany, those made of naturally white wool were often dyed, while those made from naturally dark wool were generally not. This brings up another consideration – dyeing a darker natural wool might require a more saturated dye bath to produce the desired appearance and may not have been worth it under most circumstances. And this does not even begin to consider the possibility of a trade in second-hand garments, which could have made worn or damaged garments in brighter colors available to a person of lower status than the original owner, but I am not interested in introducing any more mental contortions to justify recycling a fancy cloak from a different kit. I’ll just get a new and more modest one.

So for the moment, here is where my speculation has landed me: I think it is not unreasonable to consider that a cloak made from light-colored (if slightly variegated) wool and dyed to a muted, low-saturation coloring could represent the upper end of the possible spectrum, while at the lower end, an undyed cloak that is naturally a mottled dark brown or gray may also be appropriate. As far as the weave type, based on the overwhelming prevalence of diamond and 2/2 diagonal twill among the analyzed early medieval textile fragments from Frisia (Brandenburgh, 2010, see Tables 8a&b), the cloak should almost certainly be one of these two. I opted to go shopping for a fairly coarse diagonal twill cloak in a subdued madder shade produced from a weak or partially exhausted bath; my reasoning is that this represents a fabric that is easier to weave and requires less skill than a diamond twill (based on my conversations with actual weavers), and that imagined “cost savings” is balanced out with a dip in a dye vat that would have already been used to tint more valuable garments.

Brooch

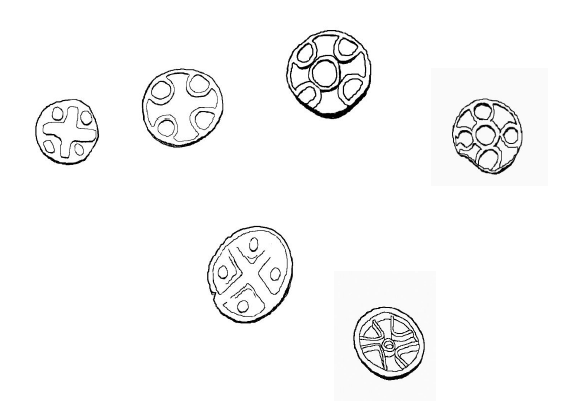

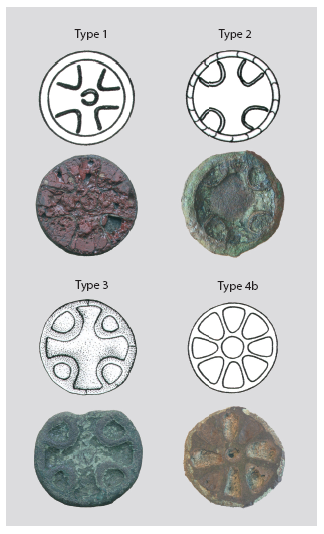

To clasp the cloak, I went through something of a wild goose chase to find an example of a common brooch type in a non-precious metal that would be appropriate for a low-middling status presentation. Again, this involves some extrapolation and guesswork, so here’s how I worked through it. In the Carolingian period, brooch types in Frisia seem to have shifted as the earlier cruciform, square-head, and small-long brooches were replaced by other types, particularly disc brooches (see Roxburgh, 2013 for a detailed discussion of typology and chronology). While some take coin-like forms, many others display Christian symbols; sometimes these were simplistic head-and-shoulders renderings of saints, and there are many versions with equal-arm crosses (see images below). These are often enameled, likely in imitation of the elaborate cloissone versions that used precious stones – some seem to echo this slightly earlier one made from cut garnet. The glass paste of the enamel is set in a copper alloy disc either using the cloissone method (wires or strips are soldered to the disc to form the cells that contain the enamel) or champleve (hollows to contain the enamel are carved or cast directly into a solid disc of metal and then filled with enamel).

Carolingian disc brooches with crosses; examples at left are metal detectorist finds from Frisia (Roxburgh 2013), while those at right were found in Denmark (Baastrup 2009).

These brooches, particularly some of the small, ungilt champleve ones, are quite crude compared to the high-end jewelry of this period (or even some other nicer enamel ones) and are common enough in the archaeological record that they were likely available to a much wider range of consumers than just the elite. Based on a metallurgical analysis, Roxburgh et al. (2014) concluded that the disc brooches with crosses appear to have been manufactured on a production scale – likely in Frankish monastic centers – and traded widely into Britain and parts of Scandinavia, opening up the possibility of a religious significance rather than just practical or aesthetic.

So what does all of this actually mean? While this brooch is not a piece of kit that I can absolutely say a modestly successful craftsman from central Frisia in 850 CE would have worn, he would have had to clasp his cloak with something, and based on the archaeological record (hundreds of metal detectorist finds in Frisia alone) and the artistic depictions in the Stuttgart Psalter, it should probably be a small round brooch of some sort. The simplistic enameled disc brooch, a sort of cheaply-made knockoff of a luxury good, seems like a reasonable bet. With that said, it is impossible to know the comparative value of something like this in period – would this have been a relatively affordable item for our Frisian, or was it the fanciest and most precious thing he owned? After reading an entire master’s thesis and a half dozen articles, I still don’t know. But after a lengthy online search for a good-quality replica in a copper alloy made with real enamel rather than resin, I will certainly treasure mine as a prized possession that was difficult for me to obtain.

Ultimately I was able to track down an artisan who makes them today – luckily, enough of them have been found in Haithabu and elsewhere in the Norse sphere that there must be a demand among the Viking reenactors? It is a replica of one of these bronze disc brooches, of a type that with a simple enamel cross in red and blue. This specific variant (known as a Wamers Type 3, see previous image) seems to be extremely widespread, even further east into Denmark, where it is the most ubiquitous type and dates to the 9th century, particularly the second half (Baastrup, 2009). It is very close to this example found at Dorestad as well. So I’m trying to lean on probability here in selecting what seems to be a very common version of a widespread, comparatively inexpensive piece of jewelry here.

Example of a Carolingian bronze cloissone brooch from Dorestad (collection of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden) and my modern reproduction (purchased from Etsy seller KATTHUND)

So, without further ado, here is the finished presentation (the legwraps still need to be dyed, but it will be another two months before I can forage nettles for this). Just for fun, let’s call this guy Frethwi – the name comes from a group of 10th century abbey records from Werden that held land in Frisian areas and includes several distinctively Frisian given names. So here’s Frethwi – he enjoys long walks on the beach, recycling old garments into funny hats with earflaps, and wearing his nice pink cloak to church since his grandpa and all the neighbors converted to Christianity.

Sources:

Baastrup, M.P. 2009. “Carolingian-Ottonian disc brooches – early Christian symbols in Viking age Denmark.” Glaube, Kult und Herrschaft. Phänomene des Religiösen im 1. Jahrtausend. Chr.in Mittel- und Nordeuropa.

Brandenburgh, Chrystel R. “Early medieval textile remains from settlements

in the Netherlands: An evaluation of textile production.” Journal of Archaeology in the Low Countries, 2:1 (May 2010), 41-79.

Brandenburgh Chrystel R. 2016. Clothes make the man : early medieval textiles from the Netherlands (dissertation). Leiden University Press.

Hagg, Inga, Gertrud Grenander Nyberg, and Helmut Schweppe. 1984. Die Textilfunde aus dem Hafen von Haithabu. Neumünster: K. Wachholtz.

Hundt, Hans-Jürgen. 1981. Die Textil- und Schnurreste aus der frühgeschichtlichen Wurt Elisenhof. Studien zur Küstenarchäologie Schleswig-Holsteins. Serie A, Elisenhof, Bd. 4.Römisch-Germanische Kommission Des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Zu Frankfurt Am Main, Institut Für Ur-Und Frühgeschichte Der Universität Kiel. Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang.

Roes, Anna. 1964. Bone and antler objects from the Frisian terp-mounds. Harlem: H. D. Tjeenk Willink and Zoon N. V.

Roxburgh, Marcus A. 2013. Castaways: new insights from the metal-detected brooches of Early Medieval Frisia. Masters thesis, University of Leiden.

Roxburgh, Marcus A., Hans D. J. Huisman, and Bertil van Os. “The cross & the crucible: the production of Carolingian disc Brooches as objects of religious exchange?” Medieval and Modern Matters 2014 5:, 117-132.

Volken, Marquita. 2016. Archaeological Footwear: development of shoe patterns and styles from Prehistory till the 1600’s. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Zimmerman, Hanna. 2010. “Two Early Middle Age caps from the dwelling mounds Rasquert and Leens in Groningen Province, the Netherlands”, in NESAT X, 288-290.

This is great work!

I do want to comment though that we do have evidence for the square gusset in the armpit before the 11th century, but it’s from Tunics excavated in Egypt and the Levant, not from North Europe. So sticking with just the Triangular Gore I think was a good choice.

LikeLike

Thanks! And yes, I felt that the examples you mentioned were too distant to base my interpretation on for this purpose.

LikeLike

Great post and made a reference in mine about Frisian clothing: https://frisiacoasttrail.blog/2020/10/16/haute-couture-from-the-salt-marshes/

LikeLiked by 1 person